Big Game Hunting is back despite decreasing Ransom Payment Amounts

Midway through Q1 the winds of progress shifted, and we observed a material increase in attacks on large enterprises that achieved levels of impact that we had not observed since before the Colonial Pipeline attack in May 2021. In 2019 and 2020 it was fairly common to see large enterprises become completely paralyzed by ransomware encryption. This evolved in the quarters that followed the Pipeline attack. We highlighted the key reasons for ransom payment contraction last quarter, which focused on enterprises realizing a return on security & incident response training investments, law enforcement activity, and the compounding nature of contracting unit economics within the cyber extortion industry. These factors were countered by behavioral shifts from the threat actors towards more fluid operations. These we highlighted in Q2 2022, to show how ransomware actors were treading more lightly in response to better security and LE takedowns.

Average Ransom Payment

-20% from Q4 2022

Median Ransom Payment

-15% from Q4 2022

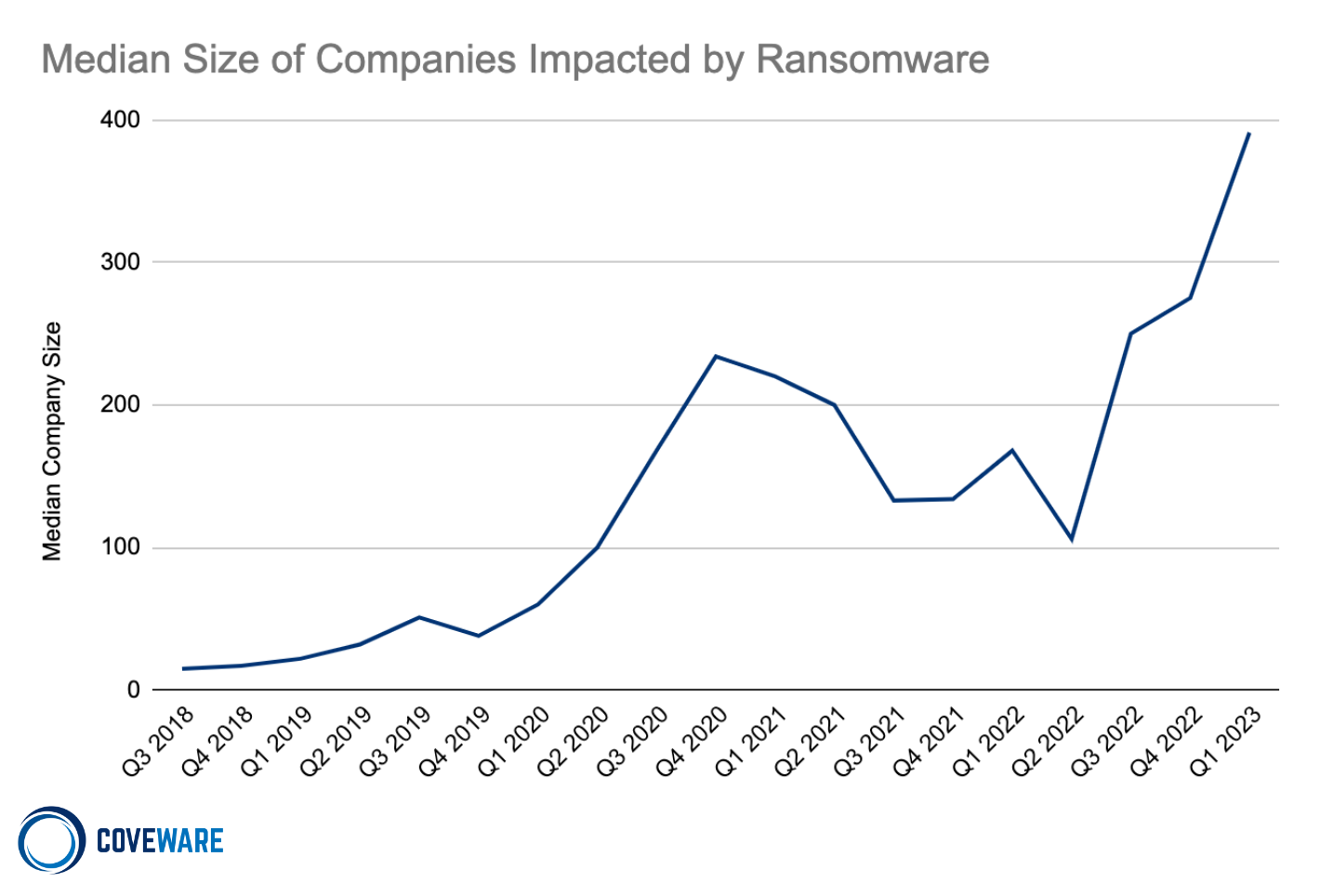

Despite declining average and median ransom amounts (Average Ransom Amount: $327,883 (-20% from Q4 2022), Median Ransom Amount: $158,076 (-15% from Q4 2022)), the median company size for a ransomware victim increased substantially (Median Company Size: 391 (+42% from Q4 2022)). We also observed a measurable increase in the number of large public companies that sustained catastrophic levels of encryption and subsequent business interruption.

Why is this happening? We are not pundits, but we have a few ideas. Given the decentralized, anonymous nature of the cyber crime economy, there are likely several variables contributing to the shift.

Factor #1: Socio-economic impact of Sanctions / Russia-Ukraine war. When the war broke out last year, we worried that financially motivated cyber crime may spike as individuals not previously involved in cyber crime, are forced into the industry by a lack of economic alternatives. The impact of sanctions on Russia is causing regular, STEM educated citizens to become unemployed, or less than gainfully employed. As a result, some of these individuals may adopt cyber crime as a means to earn a living. This would be further compounded by nation states providing a safe haven for these actions. Prior to the war there was some collaboration and coordination with western law enforcement, and some policing of the most egregious instances of cyber attacks against the west (even if they were token). Today, we can’t rely on such actions. Moreover, Russia is likely to be increasingly permissive in condoning cyber crime as the proceeds keep portions of their population earning a healthy living (so they don’t look to the state for income).

Additionally, rising inflation of the dollar and increasing layoffs within the global tech industry have given rise to financial pressure for technology professionals around the globe. While such pressure might be most acute in Eastern Europe, the tech sector is global and an increase in unemployment and cost of living may compel out-of-work technology professionals to participate in cybercrime.

Factor #2: The cyber extortion economy has been in contraction for several quarters. Given the potential uptick in participants and the perceived lack of risk, ransomware threat actors are making up for lost earnings by going back up-market. They are targeting larger companies and working to cause highly disruptive impact.

While some large companies have succumbed to these attacks, more have deflected the most damaging aspects successfully. Regardless, the attacks continue in earnest and demands are rising. In Q1 of 2023, 45% of attacks had an initial demand over $1 million. This was an all time high. Even with the increase in initial demand, companies have found their resolve and the overwhelming majority are not considering these inflated dollar amounts. Despite this, the percentage of companies that ultimately decided to pay crept up to 45%, reversing a downward trend that had spanned 4 consecutive quarters.

A good example was the relatively less successful extortion campaign carried out by the CloP group. Much like the Accellion attack carried out by CloP in Q1 of 2021, this campaign leveraged a zero day vulnerability in a similar type of product called GoAnywhere MFT. CloP claimed to have breached 130 enterprises in this attack, stealing terabytes of data from victims and holding it as leverage for extortion. In the Accellion attack of 2021, we estimate between 50-65% of victims ended up paying a ransom. Based on the approximate number of companies impacted in this year’s attack (130), and the number of logos posted to the CloP leak site who presumably did not pay (103), we estimate that only ~20% of companies paid. While this may still be a lucrative attack for the CloP group, it was far less lucrative than it would have been if 50-65% of companies paid. As discussed, companies are increasingly understanding that ransom payments aimed at suppressing the visibility of a data leak are NOT worth considering and hold little if any value (unlike payments for a decryption tool, which can be clearly measured by their relative efficacy in recovering data and minimizing the costs of disruption). An overwhelming proportion of CloP victims in this year’s attack choose to not even bother engaging with the CloP threat actors. This is why CloP did not climb the market share charts, despite impacting 130 companies in a single quarter.

Most Commonly Observed Ransomware Variants in Q1 2023

| Rank | Ransomware Type | Market Share % | Change in Ranking from Q4 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BlackCat | 12.6% | +2 |

| 2 | Black Basta | 11.8% | - |

| 2 | Royal | 11.8% | +2 |

| 3 | Hive | 7.1% | -2 |

| 4 | Lockbit 3.0 | 6.3% | +3 |

| 5 | Phobos | 4.7% | - |

| 5 | BianLian | 4.7% | New in Top Variants |

| 6 | Play Ransomware | 3.9% | New in Top Variants |

Market Share of the Ransomware attacks

Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) brands continued to proliferate in Q1 2023, and we have already seen new variants emerge such as Cactus, Akira, and Trigona. It is important to note that while we expect the labor pool to increase (the number of people earning money from ransomware), the emergence of a new variant or RaaS brand does NOT mean the affiliates of that brand are themselves new. There is no longer any loyalty from a given affiliate to a single RaaS brand. Affiliates are typically able to use several different types of ransomware in a given attack. As an example, after the Hive Ransomware operation was spectacularly infiltrated and dismantled by the FBI, we suspect Hive affiliates quickly swapped over to using BlackCat, Royal and other well known RaaS variants. Attribution has become increasingly complex, and requires defenders and incident responders to drill down below the brand label to more nuanced IOC’s and TTPs that can point to the actual people involved.

Ransomware Attack Vectors and MITRE ATT&CK TTPs Observed in Q1 2023

The TTPs and IOC’s used in Ransomware attacks are frequently repetitive and homogenous, compounding the difficulty in attribution.

In Q1, email phishing retained its standing as the number one most observed attack vector, due in no small part to the ongoing partnership between Black Basta and Qbot. Dynamic phishing campaigns are crafted to deploy the Qbot trojan within victim environments, providing the initial foothold Black Basta ultimately uses to stage and carry out their attacks (usually a combination of data exfiltration and subsequent encryption). Below are the most common TTPs observed in attacks, mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

Impact: [TA0040] Impact consists of techniques used by adversaries to disrupt the availability or compromise the integrity of the business and operational processes. Techniques used for impact can include destroying or tampering with data. In some cases, business processes can look fine, but may have been altered to benefit the adversaries’ goals. These techniques might be used by adversaries to follow through on their end goal or to provide cover for a confidentiality breach.

Data Encrypted for Impact [T1486]: Encryption of files is the most common form of impact observed. This may include forensics logs and artifacts as well that may inhibit an investigation.

Service Stop [T1489]: Threat actors often disable services related to detection, or backup replication to maximize the impact of encryption.

Data Destruction [T1485]: Most of the time, data destruction is aimed at the destruction of forensic artifacts via the use of SDelete or CCleaner. Unfortunately, sometimes ransomware actors destroy production data stores (sometimes malicious, sometimes by accident).

Resource Hijacking [T1496]: It is very common to find cryptocurrency mining software in the environments of impacted enterprises.

Lateral Movement [TA0008]: Lateral Movement by threat actors consists of techniques used to enter and control remote systems on a network. Successful ransomware attacks require exploring the network to find key assets such as domain controllers, file share servers, databases, and continuity assets that are not properly segmented. Reaching these assets often involves pivoting through multiple systems and accounts to gain access. Adversaries might install their own remote access tools to accomplish Lateral Movement or use legitimate credentials with native network and operating system tools, which may be stealthier and harder to track. The two most observed forms of lateral movement are:

Remote Services [T1021], which is primarily the use of VNC (like TightVNC) to allow remote access or SMB/Windows Admin Shares. Admin Shares are an easy way to share/access tools and malware. These are hidden from users and are only accessible to Administrators. Threat actors using Cobalt Strike almost always place it in an Admin share.

Lateral Tool transfer [T1570]: Primarily correlates to the use of PSexec, which is a legitimate windows administrative tool. Threat actors leverage this tool to move laterally or to mass deploy malware across multiple machines.

Defense Evasion [TA0005]: Defense Evasion consists of techniques that adversaries use to avoid detection throughout their compromise. Techniques used for defense evasion include uninstalling/disabling security software or obfuscating/encrypting data and scripts. Adversaries also leverage and abuse trusted processes to hide and masquerade their malware. Other tactics’ techniques are cross-listed here when those techniques include the added benefit of subverting defenses.

Indicator Removal on Host - Clear Windows Event Logs [T1070] involves 2 common event logs that get cleared by threat actors, Security and System. Security primarily records authentication, so if cleared, evidence of new account creations, remote access, or lateral movement can be lost. The System event log is helpful in identifying Service Installations, so if it’s cleared, evidence of any tools being used or stopping of services can be lost. This can be an effective way for a threat actor to cover some of their tracks.

Process Injection: Dynamic-link Library Injection [T1055] is when an actor injects their malware into a legitimate Windows process to try to avoid detection

Impair Defenses [T1562] is mainly the uninstallation or removal of antivirus software, or circumvention of anti-tampering configurations on EDR or detections software.

Exfiltration [TA0010] Exfiltration consists of techniques that threat actors may use to steal data from a network. Once data is internally staged, threat actors often package it to avoid detection while exfiltrating it from the bounds of a network. This can include compression and encryption. Techniques for getting data out of a target network typically include transferring stolen data over threat actor command and control channels.

Exfiltration over Web Service [T1567] is the most common sub-tactic, which covers use of a variety of third party tools such as megasync, rclone, Filezilla or Windows Secure Copy.

Command and Control [TA0011]: Command and Control consists of techniques that adversaries may use to communicate with systems under their control within a victim network. Adversaries commonly attempt to mimic normal, expected traffic to avoid detection. There are many ways an adversary can establish command and control with various levels of stealth depending on the victim’s network structure and defenses:

Remote Access Software [T1219]: Ransomware threat actors will use legitimate software to maintain an interactive session on victim systems. Common tools observed in Q1 were AnyDesk, TeamViewer, LogMeIn and TightVNC.

Ingress Tool Transfer [T1105]: When establishing command and control, actors will commonly install external tools onto the controlled endpoint in order to further proliferate their movement inside a network.

Proxy: Multi-hop [T1090] tactics are used to direct network traffic to an intermediary server to avoid direct connections to threat actor command and control infrastructure.

Last quarter, ~9% of impacted companies had OVER 10,000 employees. In Q1, that percentage jumped to 13%, reflecting the move up market towards larger companies. We expect this trend to continue through Q2 as threat actors invest more heavily in attacks against larger enterprises as they seek larger ransoms. Notably, 70% of attacks against this size cohort (impacted companies with over 10,000 employees) were limited to data exfiltration only - no encryption element was used.

Larger targets, while appealing to adversaries due to their perceived financial viability, also tend to have better security hygiene, proper network segmentation, and 24/7 monitoring that makes large scale encryption events substantially more expensive to execute successfully. Rather than pivot their focus to small/mid-size companies that may be easier to disrupt, threat actors have shown a preference for simply abandoning the encryption element altogether and focusing their efforts on data-theft-based extortion alone. This has become especially true in today’s climate where ransomware actors have seemingly lost their appetite for hand holding victims through the decryption element of ransomware recovery. As actors increasingly evaluate the profitability of their attacks, they are trimming down their own workload on activities that have a low probability of returning a profit.

As ransomware affiliates become increasingly fluid, preference for industry by specific groups will further blur. We note that groups such as Vice Society which almost exclusively targeted educational institutions, are now impacting enterprises across different industries. This does NOT reflect a change by the developer that controls the Vice Society RaaS. It reflects a more diverse group of affiliates that may use the Vice Society RaaS kit for a given attack against any company in any industry.